In a better — or even different — world, I would have time to read Marion Nestle’s new book, Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (and Winning) (Oxford: 2015) now. Instead I read Natalie Angier’s excellent review of it, “The Bear’s Best Friend,” (New York Review of Books, May 12 2016.)

In a better — or even different — world, I would have time to read Marion Nestle’s new book, Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (and Winning) (Oxford: 2015) now. Instead I read Natalie Angier’s excellent review of it, “The Bear’s Best Friend,” (New York Review of Books, May 12 2016.)

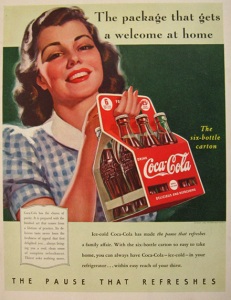

Here’s the good news: all the bad public relations against what we used to call soda pop, and even failed political attempts to suppress its sale, are working, despite the billions that the industry pours into advertising, sponsorships and lawsuits. Consumption of sugar waters is dramatically down, the sale of plain bottled water is up (not so good for plastic waste!), and obesity has flatlined for the first time since 1986. Big Soda has also tried to appear more sincere and caring: the cute polar bear ads, in which mother bear soothes her children with Coke; creating points of sale at nearly every turn; and the creation of new vending machines that allow you to mix various flavors together give those who haven’t turned against soda increased convenience and choice Meanwhile, corporate campaigns extolling exercise as the antidote to consuming excess calories convey the impression that executives at Coke and Pepsi are the good guys. The message is that you can consume as much soda as you want if only you work it off.

In 2013, a full-page ad in The New York Times declared, “At Coca-Cola, we believe active lifestyles lead to happier lives. That’s why we are committed to creating awareness around choice and movement.” In other words, Coke can be a happy choice, if you couple it with Pilates. The soda industry has poured significant resources into the exercise diversion gambit, both here and abroad. Two years ago, Coca-Cola served as a major financier for the Fifth International Congress on Physical Activity and Public Health in Rio de Janeiro, a meeting promoted by prestigious groups like the International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education (“Have you taken your 30 minutes of physical activity today?”). Dr Pepper Snapple, the third-largest soda-pop conglomerate, sponsors programs to encourage “Random Acts of Play” and the reduction of today’s “play deficit” through the distribution of sports equipment and the construction or upgrading of two thousand playgrounds across North America. Nestle estimates that Coca-Cola and PepsiCo spend about $1 billion a year supporting major sports events and associations like the Olympic Games, the World Cup, the National Basketball Association, and the National Hockey League.

“The problem is,” Angier writes, “that it takes far more exercise to counter the casual consumption of sugared soft drinks than most people realize. If you want to burn off, say, four twelve-ounce cans of Pepsi or Dr Pepper a week, at 150 calories a can, plan on tacking another seventy minutes of jogging onto your weekly workout routine just as a remedy for soda.” Although dieting and exercise are better, as it turns out, dieting is not an option if you want to lose weight. “To shed just one pound requires expending 3,500 calories, which amounts to some seven hours of jogging—all without doing what many people do when they exercise a lot, which is consume more calories.” So not drinking liquid sugar at 150 calories a can is an excellent idea, even more so for poor people who have inadequate medical care to counterbalance the health problems that sugar and overweight produce, among them heart disease, joint problems, inflammation and diabetes.

But it occurred to me to wonder: when addressing overconsumption of soda, why don’t we ever talk about hunger? Such discussions inevitably devolve reflect harsh class and racial judgements, as well as thinly veiled scorn for the presumed lack of self-control that sugar consumption seems to reveal. Yet when Angier pointed out that 1986 marks the beginning of the so-called “obesity epidemic,” I realized that she had not linked this date to poverty. Between 1970 and 1994, when the Clinton administration eliminated Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), support for poor families dropped to 53% of what it had been prior to 1970. Since 1994, food insecurity has become more extreme.

As the late Sidney Mintz observed about 17th and 18th century England, tea, coffee and sugar bolstered the capacity of the English working classes to labor for a day on very little food. Do poor people in America drink soda because they too are hungry, overworked and underpaid? As Mintz noted in his classic Sweetness and Power: the Place of Sugar in Modern History (Penguin Books, 1985), the English poor were similarly criticized for getting by on white bread dipped in sweet tea. A “nation of wage earners” in search of fuel to power a day’s work at low wages could not do without these staples, which were the cheapest food available despite the fact that both were imported. Quoting the historian of English nutrition John Burnett, Mintz describes reformers who urged the working poor to consume a more varied diet, one with meat and vegetables washed down with good English beer. Yet the poor could not afford these things. Reformers did not “recognize that white bread and tea were no longer luxuries, but the irreducible minimum below which was only starvation,” Burnett writes.

This isn’t a new thought, but it belongs in every single critique of the soda industry: the American poor, and working poor, may also drink soda to avoid hunger. Anyone who has drunk white grapefruit juice all day to prep for a colonoscopy can testify that sugar works, but no amount of physical exercise can actually work off all that sugar. As we fight for living wages, paying our workers enough to afford better, not just more food, might promote the kind of diet and health outcomes that the professional classes take for granted.

Yes, they do. I did in high school. It partly explains why in the land of thin academics I am not thin. I always figured it was a class thing.

LikeLike

Thanks for a thought-provoking post. I like your link to Mintz, but I also think it’s important to distinguish twenty-first-century hunger from nineteenth-century hunger. Historians like James Vernon have argued that before the nineteenth century, hunger was just something to endure; only mid-nineteenth-century did it supposedly become preventable as a result of “state” intervention. Today, new words like hangriness imply that being hungry can and should invoke anger–and although I realize a joking term runs the risk of trivializing hunger, I think it’s a closer rendition of our sentiments about hunger today than early modern ones. Today we *assume* that people have a right to freedom from hunger. That’s a big shift from a couple hundred years ago!

LikeLike

Good points Rachel: yet now we respond to disproportionate sugar intake through a language of addiction and market-driven consumption which is quite modern. I wonder whether it is not just as distorting to what it might feel to the hungry subject (are the phsyical feelings of hunger and overwork different over time, and do they shift as cultural constructions of hunger change? This would be agreat subject!). We have ample evidence that the modern poor also endure hunger and devise strategies to “cure” it in relation to their limited access to food. Furthermore, we also know that middle class teens pushing through a ten hour school day that begins at 6 a.m. are now drinking caffeinated colas, Red Bull and super-sweet Starbuck drinks to acquire what they call “energy.” Might a 64 ounce Coke at 99 cents do the same thing for someone cleaning houses? What if, regardless of how the right not to be hungry is perceived (and I agree with you about that change) the actual condition and cures for hunger haven’t?

LikeLike

Interesting. Coke, hunger, obesity, economic injustice, the labor movement and Latin America have a fascinating and fraught relationship. Coca Cola has a long history of labor conflicts in Latin America, and its product has been focused on by President Peña Nieto of Mexico who imposed new taxes on soft drinks in an attempt to limit their consumption by Mexicans, who are among the most obese populations in the world — more obese than North Americans, if you can believe it. It is a land where Victor Medina of the Examiner estimates that nearly 100 thousand people have died of starvation in the last decade. In Latin America Coke is seen as synonymous with American-style capitalism, as Hugo Chávez famously said “Venezuela can live without Coca Cola.” Bolivian President Evo Morales equated Coke with selfishness and wanted to ban it in 2012, but that not only didn’t work out, but rang as ironic considering that his plan was to replace it with a local (and awful) peach flavored soft drink — and the fact that thousands of the starving in his country chew coca leaves to keep from falling over. Coke’s sales in Latin America are noticeably down now, but not because poverty and hunger are down, according to Patricia Rey Mallén in the International Business Times, but rather because of offense taken by religious groups in Mexico in particular against comments made by Spain Coke CEO de Quinto about what he considers to be fanaticism amongst religious groups in the country. In response, the hashtag #boikotcocacola was born, and thousands of people throughout Latin America swore to stop buying it. Ironically, Coke is now moving over to water as its new “real thing”, and trumpets its sustainability work while simultaneously co-opting water resources in poor areas — to transform it into its killer beverage.

LikeLike